In the lead-up to COP30 in Brazil in November, the United Nations Secretary-General delivered a stark warning message: ‘We are on course to overshoot the 1.5°C threshold within the next few years — a failure with grave consequences such as irreversible tipping points, whether in the Amazon rainforest, the ice sheets of Greenland and western Antarctica, or the world’s coral reefs.’

India also faces heightened vulnerability to climate change, with impacts ranging from extreme heat to the spread of vector-borne diseases. In 2024, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) reported the hottest year on record, with a global mean near-surface temperature 1.55 ± 0.13 °C above the pre-industrial average. India experienced extreme weather on 88% of days that year, with devastating outcomes: over 3,000 fatalities, 3.2 million hectares of crops impacted, upwards of 235,000 homes destroyed, and more than 9,000 livestock lost.

“Everyone in India is now vulnerable to climate change impacts, from extreme heat to vector-borne diseases. Dr. Soumya Swaminathan, Former Deputy DG, World Health Organization speaking at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan

India’s Economic Risk due to Climate Change

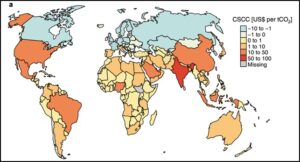

Although India’s emission intensity per capita is significantly lower than the major emitters such as the USA, and P.R of China, India is expected to face the highest economic impacts from climate change, measured by the Social Cost of Carbon (SCC). SCC represents the present value of future damages caused by a one tonne increase in CO₂ emissions within a given year. Its calculation spans a wide array of projected impacts: from diminished agricultural productivity and health effects to property damage, disaster frequency, energy system disruption, conflict risk, environmental migration, and ecosystem services loss. The SCC framework helps policymakers to compare climate change mitigation costs with long term benefits.

In 2023, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) assessed the global SCC at US$190 per ton of CO₂ emissions, meaning each additional ton leads to $190 in climate-related damages. This estimate is based on long term predictions of climate change related damages till year 2300 and low discount rate of 2% to account for uncertainty in long term impact.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) anticipates, under a worst-case scenario, that annual global GHG emissions could rise from 37 billion to 120 billion tons by 2100. Based on the worst-case emission scenario and a global social cost of carbon (SCC) of US$190 per ton of CO₂ emissions, the present value of cumulative damages is estimated to exceed $1 quadrillion worldwide.

According to another model estimating Country-level SCC, India has an SCC of US$86 per ton of CO₂, followed by the US at US$48, Brazil at US$47, and both the UAE and China at US$24 each. This indicates that, based on this model, India faces the highest estimated economic impact from climate change among the countries listed [refer Figure 1].

India’s Climate Action: Panchamrut

The Glasgow Conference (COP26) marked a pivotal chapter in India’s climate mitigation efforts. At this conference, India declared the Panchamrut—five major climate goals—including a reduction of 1 billion tons of emissions by 2030 and reaching Net-Zero by 2070.

First-Generation Ethanol: Social, Environmental & Economic Benefits

A core pillar for achieving the Panchamrut goals is transitioning from fossil-based to renewable energy sources, with biofuels playing a central role in decarbonizing the transport sector. India reached a 20% ethanol blending with petrol in 2025, five years ahead of schedule. This initiative resulted in foreign exchange savings of approximately INR 1 lakh crore, a reduction of about 500 lakh metric tons of CO₂ emissions, and increased farmers’ incomes by INR 90,000 crore over the past decade, all while bolstering energy security.

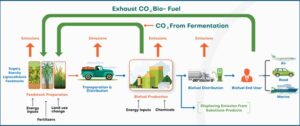

Currently, nearly all of the ~1,000 crore litres of ethanol blended with petrol for E20 comes from first-generation (1G) feedstock, such as sugarcane, maize, and rice. A study on life cycle emissions of Ethanol across the value chain [refer Figure 2] done by NITI Aayog has said that GHG emissions in case of use of sugarcane and maize based Ethanol are less by 65% and 50%, respectively than those of petrol.

Typically, use of each litre of 1G Ethanol results in roughly 1 kg of CO₂ emissions avoided. On an annual basis, using 1,000 crore litres of ethanol under the E20 initiative translates to 100 lakh metric tons of CO₂ emissions avoided.

While the E20 initiative is recognised for reducing emissions and positively influencing the economy, its role in decreasing climate-related economic damages—by cutting CO₂ emissions—receives less attention. The Social Cost of Carbon (SCC) framework measures these prevented damages by giving them a monetary value, which is illustrated by the following formula:

Avoided economic damages = Avoided CO₂ emissions x SCC

With India’s SCC at US$86 per ton and an annual CO₂ reduction of 100 lakh metric tons, the E20 initiative is expected to avoid about INR 7000 crores in climate related economic damages each year.

Second-Generation Bioethanol: Enhanced Potential Benefits

While 1G ethanol has delivered significant benefits such as energy security, reducing the Carbon Costs, savings of foreign exchange etc., second-generation (2G) bioethanol—produced from lignocellulosic biomass and agricultural residues such as rice straw and bagasse—holds even greater promise. 2G ethanol from rice straw typically has 30% to 40% lower lifecycle carbon intensity than 1G ethanol, while also supporting energy security and rural economic growth. Typically, each litre of 2G Ethanol from rice straw prevents about 1.5 kg of CO₂ emissions and saves roughly INR 10 in avoided climate-related economic damages (based on India’s SCC of US$86/ton).

Despite its substantial environmental and socio-economic benefits, the commercial adoption of second-generation (2G) ethanol faces significant challenges. The primary barriers are the higher capital investments and operating costs associated with 2G ethanol production as compared to first-generation (1G) ethanol, which benefits from government mandates and fixed pricing mechanisms.

Recognizing the potential of 2G ethanol, major Oil Marketing Companies in India have nevertheless initiated efforts to establish 2G ethanol production plants. These efforts are driven not just by the promise of reduced carbon emissions but also by the broader socio-economic and environmental advantages that 2G ethanol offers.

One notable example is the recent commissioning of a 2G ethanol facility by Indian Oil Corporation Ltd., with a capacity of 100,000 litres per day. This plant utilizes rice straw as a feedstock and operates using technology developed by Praj Industries Ltd., highlighting the growing commitment within the industry to scale up 2G bioethanol production despite prevailing commercial challenges.

Improving Economics of Biofuel Production

A typical bioethanol economic model in India includes capital and operating costs, feedstock expenses, and revenue streams from bioethanol and co-products, but does not account for the benefit of avoided carbon costs.

By integrating SCC into economic modelling for 2G ethanol plants—and recognizing avoided climate-related economic damages as a “Climate Dividend” in corporate impact accounting—the viability gap for 2G projects could be narrowed. While this amount may not fully close the viability gap, it can stimulate demand and alleviate government subsidy burdens for 2G Ethanol projects.

The SCC framework can also enhance ROI modelling for a range of emerging biofuels, including Compressed Biogas, and Sustainable Aviation Fuel, which may face hurdles in achieving viability.

Carbon Price of Advanced Biofuels

At COP29, an agreement was reached to establish a global Carbon Market. This initiative offers significant potential for the Indian biofuel sector, as second-generation (2G) biofuels, Compressed Biogas and Sustainable Aviation Fuel are expected to be eligible for Carbon Credits, thereby enhancing the commercial viability of advanced biofuel production.

The Indian Carbon Market (ICM), set to launch in early 2026, will enable industries to generate, register, and trade carbon credits for emission reduction. Integrating a Social Cost of Carbon (SCC) framework into the economic modeling of advanced biofuels can help set benchmark prices for carbon credits linked to 2G biofuels in India.

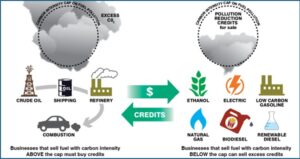

In the United States, initiatives such as the Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) program already provide opportunities for biofuel producers to generate revenue through Carbon Credits [Refer Figure 3]. Within this framework, credits are determined using life cycle assessment models that measure avoided emissions relative to traditional fossil fuels. These credits promote biofuel production, as they can be sold to other obligated entities participating in the LCFS programme, which is enforced across several U.S. states.

Biofuels driven Energy Transition

The E20 initiative has accelerated India’s energy transition and has paved the way for adoption of emerging biofuels such as 2G Ethanol, Compressed Biogas and Sustainable Aviation Fuel. Evaluating Biofuel investments by jointly considering financial, climate, and social factors—including integrating the Social Cost of Carbon into economic models—can offer a more comprehensive perspective. This approach will speed up the decarbonization of India’s transport sector.

Amol Nisal leads strategic growth and transformation initiatives at Praj. He has contributed in developing NITI Aayog’s analytical tool, ‘India Energy Security Scenario 2047 (Ver. 1)’, which assesses the comprehensive impact of India’s green energy policies. His writing focuses on Energy Transition, Sustainability, Carbon Markets, and Biofuels.

Figure 1: Country-specific SCC

Figure 2: Life-Cycle Analysis of Biofuel

Figure 3: Typical Mechanism of Carbon Credits