Insight Focus

Russia’s improved agrarian self-reliance has been seen as a triumph, reaping the name Fortress Russia. Fortress Russia was, however, built on imported technology, animals and even seeds. Russia faces a new reality, one of increasing isolation – the question is can Fortress Russia survive?

Russia’s agricultural output has drastically increased across the last decade as the country’s charged towards food self-sufficiency. Nevertheless, many of these improvements relied on a wide array of imported inputs, which are near impossible to source following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Can Fortress Russia survive as it finds itself increasingly isolated from the international trading sphere?

Russia’s Push for Food Self-Sufficiency

Russia was heavily sanctioned by Western nations following its annexation of Crimea in 2014. Following this, Russia heightened its push for food self-sufficiency, and embargoed western food imports.

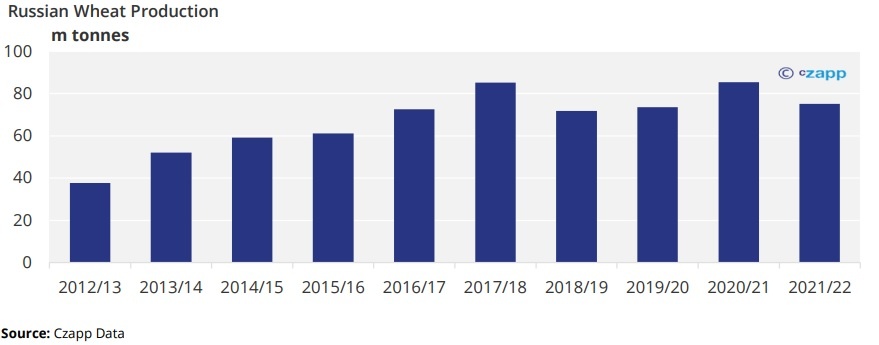

Food staples, meat and grains, were the focus. Russia’s wheat production jumped from 37m tonnes in 2012/13 to 75m tonnes in 2021/22 and its meat production went from 8.5m to 10.9m tonnes.

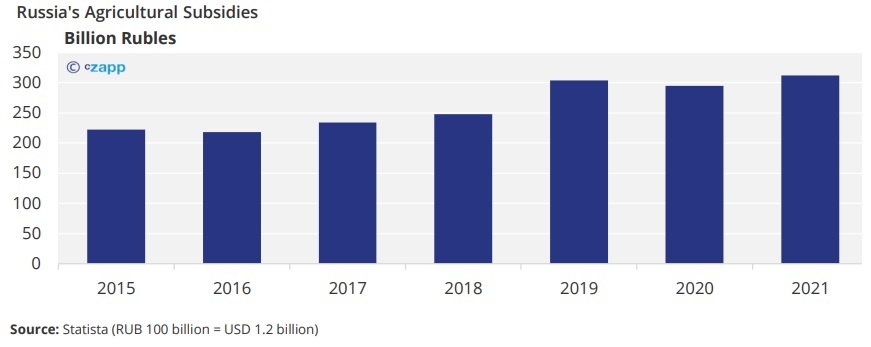

These increases were achieved as the government invested heavily in agriculture. Between 2013 and 2020, Russia’s agricultural budget went from USD 1.98 billion to USD 4.25 billion.

Farmers were offered subsidies to help them improve their practices. Russian farmers began using more imported tractors, combine harvesters and milking equipment, along with other machinery not manufactured in country.

Farmers also imported high-grade pedigree animals for beef, pork, and dairy farming. By 2019, Russia was importing over 45,000 dairy cows a year from Europe, double the rate seen just three years prior. It’s now common practice for Russia’s dairy farmers to import cattle from Western Europe as they produce higher quality milk, and more of it.

Russia’s spree of imports extended onto seeds. Instead of developing higher-yielding, pest-resistant varieties, Russia turned, once again, to Western Europe for quality seeds. This boosted Russia’s agricultural yields.

Spot the Pattern?

The Russian government applies over-simplistic quantitative metrics based on the final outcome to assess selfsufficiency rather than looking at the whole production process and the quality of the outcome.

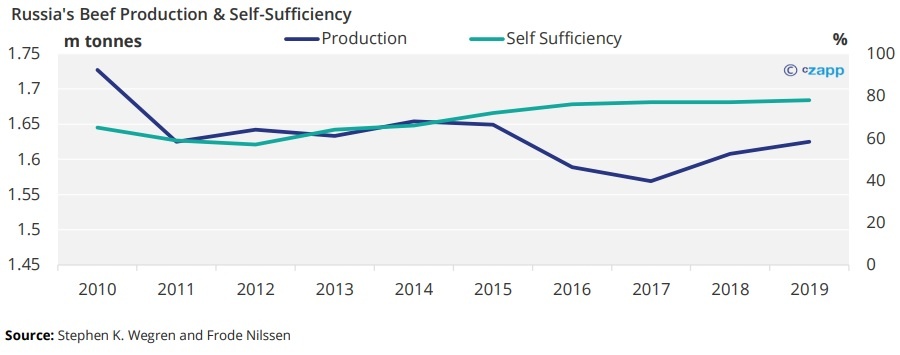

Under this, one could argue that Russia’s charge towards beef self-sufficiency was a success, whereas in fact, Russia’s self-sufficiency has improved as consumption has dropped.

Cheese is another example. Self-sufficiency has increased on the back of heightened production, but only because a lot of Russian producers now use palm and other vegetable oils instead of milk fat, hampering quality.

A 2015 study conducted by Russia’s Federal Service for Veterinary and Phytosanitary showed that 78% of Russian cheese is falsified, with some samples not containing any milk fat, only palm oil.

Andrey Danilenko, Board Chairman of the National Union of Milk Producers, has also revealed that the use of these oils is connected to the drop in the profitability of milk processing seen in recent years.

Although this looks like cheese self-sufficiency on the surface, it has an adverse impact on the Russian dairy industry, with those not willing to using palm oil suffering huge losses.

Russia is Highly Reliant on Imports

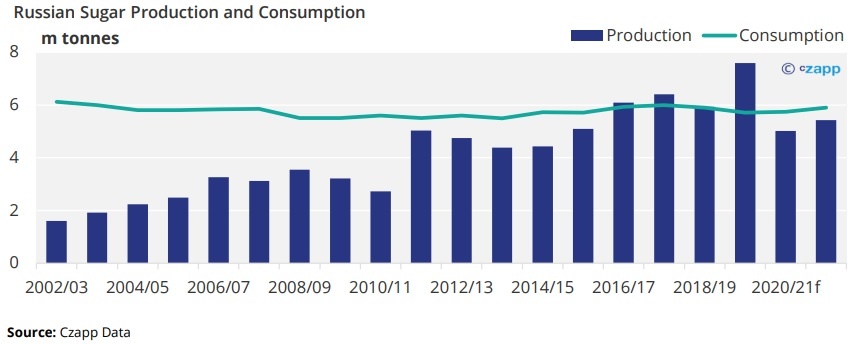

Beyond this, there are instances where Russia has boosted self-sufficiency in one area at the expense of its independence in another. For example, Russia is normally self-sufficient in sugar but more than 95% of its beet seeds are imported.

The picture is much the same elsewhere. According to Viktor Yakushev, former Director at the Agrophysical Research Institute, between 50-70% of Russia’s oil-bearing crop seeds are imported, along with a further 40-50% of its potato and vegetable seeds. And just this week, Inferfax quoted Russian President Vladimir Putin as saying Russia will “allot no less than an additional RUB 5 billion (USD 60.5 million) this year to support seed production and breeding centres.” It seems even Putin is acknowledging that more needs to be done.

This is significant because, as the Ruble devalues, input costs for Russian farmers increases. This could mean some farmers can’t afford high-quality seeds, or are forced to sacrifice the quality of one import (e.g. machinery) for another (e.g. seed).

Price aside, sanctions (both official and self-imposed) mean the usual Western suppliers are avoiding Russia. Whilst food products are immune from sanctions, seeds are not, and some companies have suspended seed exports, which bodes poorly for plantings set to commence within 6-12 months.

Russia may also struggle to source pesticide and pedigree animals, with the impact of the latter particularly pronounced for the dairy industry.

These examples reveal that Fortress Russia is not actually as self-sufficient as it may appear on the surface. With supply of key agricultural inputs disrupted, Russian yields should decline, squandering the gains made since 2014.

Beyond inputs, major manufacturers of agricultural machinery have either withdrawn themselves from the Russian market or paused operations following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Notable instances include John Deer, CNH Industrial, Claas, Kubota, and JCB.

Even if some of the companies recommence operations in Russia, it’ll not be easy for them. Some of these companies, such as Claas, produce their tractors in Russia. However, chip exports should be hit hard with both South Korea and Taiwan, the two largest chip producers in the world, sanctioning Russia.

Of course, Russia can try to start producing its own tractors, but it’s struggled to do so in the past. In fact, a previous attempt saw Russia import the required parts from the Czech Republic.

Even if Russia did improve in this area, sourcing parts internationally could be difficult, or near impossible. It’s also not just limited to tractors and harvesting machinery. The equipment required for milking, cheese production and other agricultural process also comes from overseas.

Some of this equipment could come from China and India, but this alteration would likely take time. Indian and Chinese companies won’t want to be seen as aiding Russia in skirting sanctions. Such large changes will also take longer to implement than regular servicing of machinery would.

That said, it should be a few years until Russia truly feels the impact of reduced ag-tech imports once machinery begins to break and parts need replacing. That said, we may see yields decrease in the coming seasons on the lack of this machinery.

Agricultural Investment at Risk from Economic Decline

Although Russia remains heavily reliant on inputs, significant government investment has helped the country boost yields in recent years.

This investment dwindled through COVID, though, and may not pick up now Russia has invaded Ukraine. Russia’s economy has been hit hard by economic sanctions and reduced international trade. If these issues persist, the government will have less financial power, meaning the farmers will have less support. Are the days of ‘Fortress Russia’ drawing to a close?

Concluding Thoughts

- Russia’s agricultural industry faces many challenges and shouldn’t escape the current situationunscathed.

- The industry relies heavily on imports of seeds, livestock, and agricultural machinery.

- All of these are off the table following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

- Investment in the sector also dropped in COVID and may dwindle with Russia’s economy fighting tostay afloat.

- This is bad news for Russia, but also the world which had relied on Russian food exports.

For more articles, insight and price information on all things related related to food and beverages visit Czapp.