Anyone dealing with the after-effects of a sugar high, and the health crisis associated with it, knows that a sugar-management programme is critical. Sadly, the government’s plan to deal with India’s sugar high—and the Rs 22,000 crore of farmer dues associated with this—doesn’t have anything to wean away farmers from sugar. Like many other government plans, the attempt is only to reduce the impact for the moment, and leave the rapidly-growing crisis for another day. While unduly high sugarcane prices are the main reason for why sugar mills can’t clear their Rs 22,000 crore dues to farmers, the government’s package is for just Rs 8,500 crore and that number too is based on significant over-estimation of the benefit—in other words, the package is not going to help much in even the short run.

The package includes an interest subvention of Rs 1,332 crore on Rs 4,440 crore of loans to the industry to set up more ethanol capacity—while the loans have to be repaid by industry, the package seems to take into account this as well. The interest subvention is over five years, but seems to have been fully added as well; industry also argues that the buffer stock subsidy is based on a lower cost of production than the actual. In other words, it is not clear how the plan will help mills pay farmers Rs 22,000 crore quickly. Higher ethanol prices will help mills raise revenues, but raising this capacity is a five-year plan. The old practice of supply quotas for each mills has been revived to lower supplies and raise prices—while this has helped raise sugar prices by Rs 4-5 per kg, given this month’s quota of 2 million tonnes, this raises mill revenues by just Rs 1,000 crore in June.

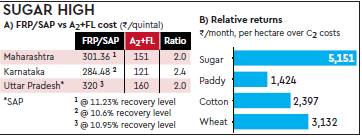

Only a twelfth of the buffer stocking subsidy of Rs 1,250 crore—mills will hold 3 million tonnes of buffer stocks and the government will pay the interest cost of holding this—will be available every month. The main point is that the convoluted new plan—including the reintroduction of pre-reform sale-quotas for each mill—doesn’t address the main issue of the massive pampering of sugarcane farmers. Indeed, while sugarcane FRP has been raised by 83% between 2009-10 and 2017-18—it is expected that the new FRP may be Rs 275 per quintal as compared to Rs 255 right now—the ex-mill sugar prices have risen by less than 6%, making it clear what the root of the problem is. While the government has announced a plan to raise minimum support prices (MSP) for all crops to at least 1.5 times the A2+FL costs, the Fair and Remunerative Price (FRP) for sugarcane is already two times A2 + FL costs in some states and even more in others (see graphic).

Based on the current FRP of Rs 255 per quintal (at a 9.5% recovery rate), India’s cane prices are 70-80% higher than those in Brazil, the world’s largest sugar producer. In fact, the CACP report on sugarcane pricing has an interesting table on relative profitability of various crops—it does this for A2, A2+FL and C2 costs. At an all-India level, it finds sugarcane farmers get gross returns of 136% based on A2+FL costs versus 102% for wheat and 58% for paddy. In terms of net returns—that is, those based on C2 costs—the returns are 52%, 27% and 12%, respectively. Since the sugarcane crop cycle is much longer than that for other crops—12 months versus 4-6 for others—the CACP also calculates per month returns for various crops. Even then, sugarcane tops the list with Rs 5,151 per hectare per month, based on C2 costs, versus Rs 3,132 for wheat, Rs 2,397 for cotton and Rs 1,424 for paddy (see graphic).

In Maharashtra, where most of the water is used up by sugarcane, farmers make Rs 4,954 per hectare per month (C2 costs) versus just Rs 737 for cotton and Rs 173 for wheat. Apart from sugar, a big demand area for cane is ethanol, especially when it is legally mandated that this be mixed with petrol/diesel—India does 5% doping, but Brazil does 25%. High cane prices, however, pose a problem here as well. While mills say they need an ethanol price of around Rs 52 per litre to produce it directly from the cane juice—right now, it is produced after the sugar has mostly been extracted—the fact is that the pre-tax price of petrol/diesel is just Rs 37-40 per litre. In short, the only viable solution to India’s sugarcane problem centres around lowering its prices dramatically, but the government is not even thinking along those lines—and if it was, the fact that the BJP did badly in the cane-producing Kairana by-poll has put paid to that. While sugarcane farmers who have Rs 22,000 crore of dues are portrayed as being victimised by sugar mills, this ignores the fact that, with high prices and assured buyers, they are pampered beyond belief.