Czapp Insight Focus

Aversion to buying Russian metals driving up global prices. Aluminium packaging shortage challenge for food, drink industry. Other materials such as PET could fill packaging gap.

Russia is a leading source of metals, especially aluminium. So, since its invasion of Ukraine, many global metals prices have surged as energy costs skyrocket. One of the most concerning for food and beverage companies is the price of aluminium, which is commonly used in packaging. As supply crunches continue with little new capacity coming online, food and beverage companies may need to look to alternative materials, such as PET.

Favourable Aluminium Characteristics Lead to Higher Prices

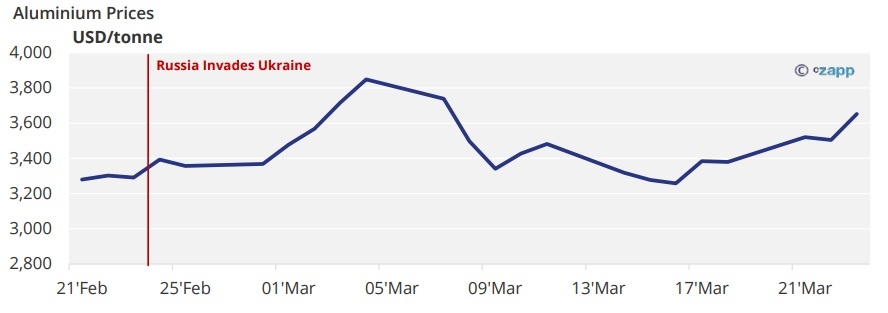

Global metals prices have been rallying since the end of February in another fallout from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The price of aluminium rose to a high of 3,849 USD/tonne on 4th March.

While prices have now stabilised somewhat, they remain elevated, closing at 3,653 USD/tonne on the 23rd March. By contrast, the average price on the London Metal Exchange was 2,479 USD/tonne for 2021.

Rising energy prices are partially to blame for the metal price increases, due to the energy-intensive nature of production. There have also been increases in the cost of alumina — a key feedstock — due to higher production costs and a reduction in Chinese manufacturing volumes.

Supply-Demand Imbalance Pressures Market

The world consumes about 180 billion aluminium cans of beer and soft drinks every year. Aluminium foil packaging is also gaining ground in the food and beverage industry.

Not only is aluminium highly recyclable, with 75% of that ever produced is still in use, it’s flexible, lightweight, impermeable, and cost-effective, making it an ideal product for food packaging.

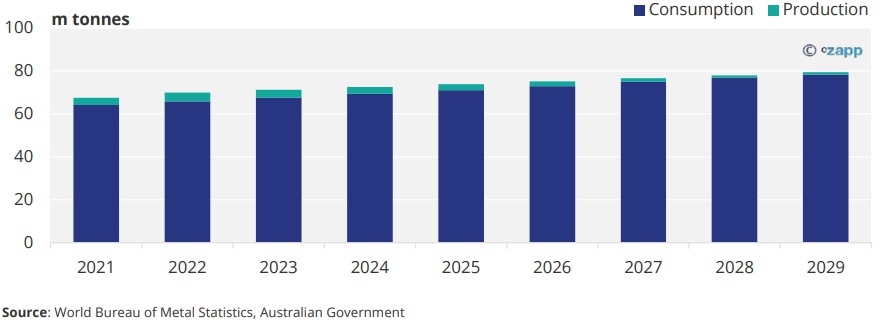

The increasing desirability of aluminium means capacity growth is barely keeping pace with demand. Aluminium consumption is only expected to increase. If consumption and production continue according to projections, aluminium supply will only become more constrained by 2029.

Gap Between Consumption and Production Projections

Sanction Concerns Could Impact

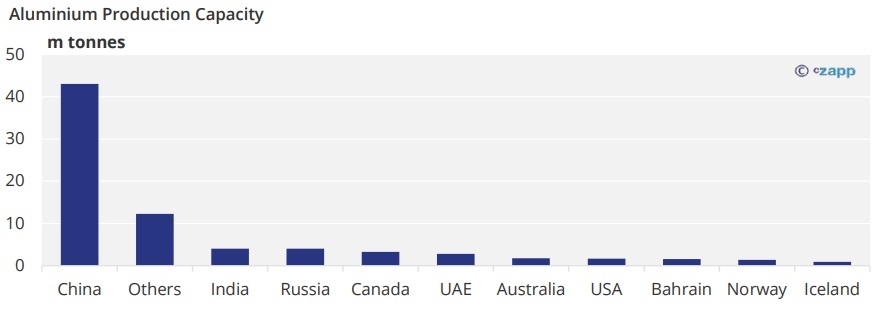

Russia is home to Rusal, which manufactures about 6% of both the world’s aluminium and its metallurgical alumina.

Rusal Plant

According to its financial statements for the 1H’21, Rusal sold around 41% of its production to Europe and 8% to America.

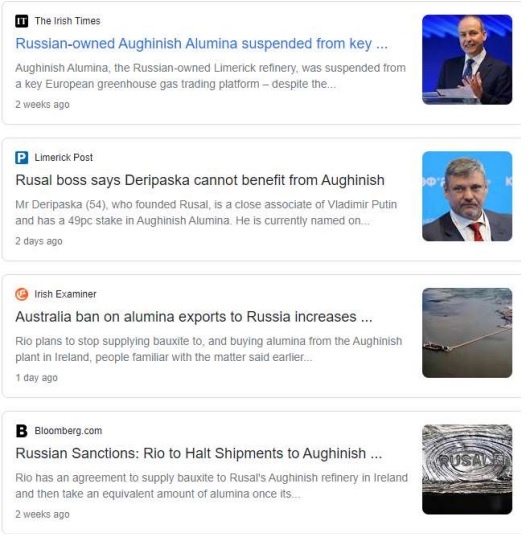

Although sanctions do not apply to Rusal or aluminium, billionaire Oleg Deripaska has been sanctioned by both the UK and Australia. Deripaska has links to Rusal, sparking fears that the company’s aluminium supply may be caught up in the crossfire.

Rusal owns Ireland-based Aughinish Aluminia, but last week, the Irish Prime Ministry reassured workers that no sanctions have been applied by the European Union. However, he noted that sanctions are under the jurisdiction of the EU rather than Ireland, meaning “Ireland cannot and does not introduce unilateral measures.”

There are also other implications for the Irish producer. Rio Tinto has halted two supply agreements with Aughinish as it seeks to sever ties with Russian companies. Aughinish was also suspended from trading on the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) platform — a key tool that allows companies in high CO2-emitting industries to cover their emissions or face fines.

Rusal also operates the Ukrainian Nikolaev alumina refinery, which produced 1.8 million tonnes in 2021. The refinery has been closed for the past two weeks, exacerbating already-tight alumina supply. Beyond this, Rusal owns aluminium and alumina production facilities in Armenia, Sweden, Jamaica, Guinea and Australia, which may potentially be affected by self-sanctioning.

Rusal’s Russian facilities also account for 97% of its total aluminium and 37% of its total alumina output. Even without sanctions, trading with Russian companies has been complicated by their exclusion from the SWIFT international payment system. If Rusal’s aluminium supply is jeopardized, this could remove about 4 million tonnes of aluminium from an already tight market.

There is also a risk that Rusal may not be able to source enough inputs to produce its aluminium after Australia banned alumina and bauxite exports. Australia accounts for almost 20% of Russia’s alumina supply, which is not abundant in Russia or its neighbouring countries.

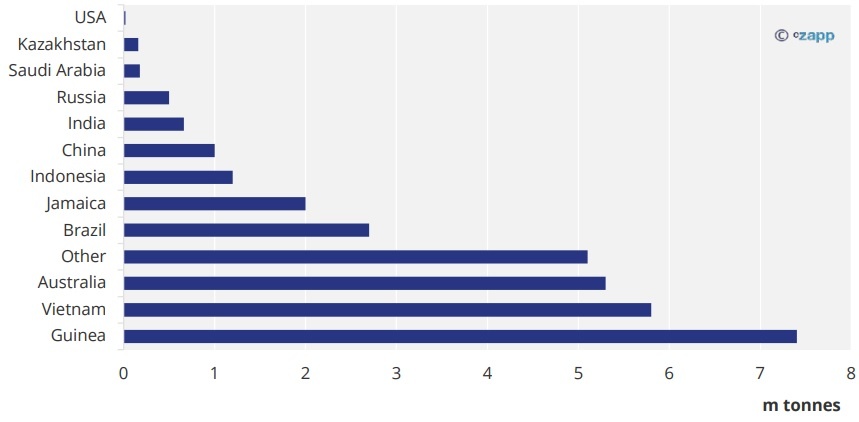

Bauxite and Alumina Reserves in 2020

Rising Energy Costs to Further Push up Prices

Although aluminium is known for its recyclability, the production process for primary aluminium is energy intensive. Production of the metal accounts for 2% of the world’s total energy use, with about 17MWh of electricity required to produce 1 tonne of aluminium. That’s the equivalent to running a central air conditioner 24 hours a day, seven days a week for six and a half months. In the US, average annual household electricity consumption comes in at just over 10MWh.

Natural gas prices are continuing to rise through 2022. Given that Russia is the second-largest producer of natural gas in the world behind the US, this trend is unlikely to reverse any time soon.

Henry Hub Natural Gas Spot Price

Further rises in natural gas prices driven by supply pressures are likely to push up the price of aluminium even further in the near future.

New Supply Could Improve Situation

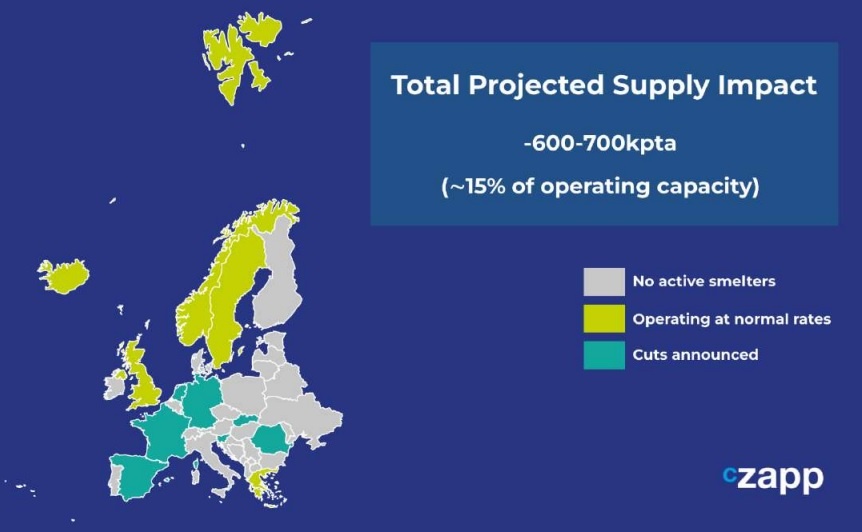

It would seem the main way to solve supply issues would be to bring online more production capacity. But according to major aluminium smelter Alcoa, a 1.4 million tonne deficit will persist for 2022, while global stocks will remain at record lows. Producers across Europe have already announced cuts equating to around 15% of supply capacity.

Alcoa expects to make between 2.5 million tonnes and 2.6 million tonnes of aluminium shipments in 2022, compared with 3 million tonnes in 2021. Rio Tinto already recorded a 1% year on year drop in aluminium production to 3.2 million tonnes in 2021, while alumina production fell 2% to 7.9 million tonnes.

Importantly, none of the major aluminium miners have significant projects in the pipeline that would build up capacity. Potential mines tend to undergo a lengthy exploration stage, which requires substantial investment and does not guarantee results, meaning many companies are reluctant to take the risk. Even after the exploration stage, development and construction of the mine generally takes from five to 10 years and costs hundreds of millions of dollars.

PET Could Bridge Supply Gaps

Given that it is a petrochemical, PET is traditionally seen as a less environmentally friendly packaging option than aluminium. Aluminium also has the advantage that it can be recycled infinitely, while PET bottles have limitations due to degradation of quality.

But the truth is that aluminium can generate more emissions than PET. In fact, when less than half is recycled, a newly manufactured 330ml aluminium can has a footprint of between 331g and 1,300g of CO2 – much bigger than a PET bottle with very low recycled content, which comes in at 196g to 330g. With very high recycled content and very high recycling rates, both come out equal at between 35g and 85g of CO2.

Not only can PET compete on emissions, but it also tends to be much cheaper for food and beverage manufacturers. That being said, this may become less of an advantage as oil prices and by extension petrochemical prices continue to rise due to Russia’s position as a major producer. Transportation is also much less costly for PET due to the fact that it is a lighter weight material than aluminium.

Concluding Thoughts

- With an absence of new capacity coming online and supply worries around Rusal, demand for aluminium is outpacing supply.

- Rising energy prices compounded by the Russia-Ukraine crisis threatens to push aluminium prices up further.

- Food and beverage manufacturers should start looking to alternative packaging materials, such as PET to plug supply gaps.

For more articles, insight and price information on all things related related to food and beverages visit Czapp.